Who is Brother? Who is Uncle Bim?By Anthony Buccino

The four-room house was plenty, it

had three bedrooms; one for four sons, one for three daughters, and one for the parents. |

|

|

BELLEVILLE NJ -- “If only this kitchen could talk!” Aunt Connie said when I visited her in April. She was 83 and still living in the same house where she was born. Except for the addition of a kitchen where we sat, a first floor indoor bathroom and a back porch, it was the same four-room house her father, Raffella Aliperto, built for his budding family shortly after the turn of the century.

The last time a tax assessor came, he wanted her to show him the rooms in the attic. She told him there was no attic. He was adamant as tax assessors are supposed to be. The front of the house had a pitch, and the back of the house had a pitch, therefore there must be a second floor with more rooms to tax. On the west side of the house is an old garage with a foot of space from her house. It is barely enough room to swing a hammer, let alone look up and see the roof. The backyard is virtually landlocked with Mr. Edison’s plant bordering the rear, and the neighbor on the east blocking other access. To get to the backyard from the street, you have to go in the front door, through the house and out the back door. She led the assessor down the hall off the kitchen to the door that led to the cellar stair. He demanded she open it and show her the stairs to the attic. “There is no attic.” She repeated. When he saw the stairway, he looked for a hidden panel and when he found none, he conceded there was no attic and no taxable rooms upstairs. “The front and rear roofs pitch to the center where they drain,” she explained to the disgruntled assessor, “I grew up here, I should know if there is a second floor.” Raffella and his wife Madeline Penna came from Marigillano, Italy. In Belleville, New Jersey, United States of America, they had seven children and lived in a four-room house Raffella built on Alva Street adjacent to a factory owned for many years by Thomas Edison himself.

As the work whistles blew and the smoke spewed from the factory in their landlocked backyard, Raffella, like most illiterate Italian immigrants worked as a laborer to support his children, Sam, Celia, Frank, Tom, Dan, Connie and Lucy. Most of the projects Raffella worked on to support his family are lost to renovations, demolition and long-forgotten memories of a weary father pointing to places he once dug ditches and carried a heavy yoke. One place where he worked stands today and is pointed out to descendants who happen to Alva Street to ask where Connie’s father worked. He helped build Sacred Heart Cathedral in Newark, near Branch Brook Park where each spring Cherry Blossom trees bloom and fill the air with sweet scents and pink hues and petals that may lighten the labor of men like Raffella who came to America to raise families in a better life. The Pope himself said Mass there in 1995. Aunt Connie’s kitchen seemed smaller than I remembered it from my boyhood visits. She wept as she recalled the family, come and gone, good friends and relatives who drank coffee and ate the finest Italian pastries and cooking and chatted the night away for birthdays, anniversaries and for no reason at all.

Together their foils sparks light up lonely nights of tender memories. “Only JoAnn comes to visit. I keep the bills here so she can write them.” Aunt Connie raises gnarled hands, “With this arthritis and my stroke, I can’t write.” For the longest time Aunt Connie was a part owner of Embroidery Masters on Belmont Avenue in Silver Lake. She and the other ladies did fine embroidery. When my sister Lucille got married in 1967, Aunt Connie presented her a fine-embroidered bedspread. It was a work of art and the envy of the family. Aunt Connie and Uncle Jim had raised three children here in this house. Uncle Jim died in 1960 at age 56 – a quirky age that many of the siblings succumbed to cancer. Of his children, Frankie was oldest. He was one of several Frank Cocozzas in the family, all named for my great-grandfather. I knew him as Cousin Frankie in Brazil. His sisters JoAnn and Ria had all boys. Aunt Connie could name not only her grandchildren but relatives from both branches of the family tree. The Alipertis had grown up with the Cocozzas, so all her life they were one big Italian family. She knew all their stories and could remember them, their birthdays, and their children’s birthdays too. How Aunt Connie could remember. She remembers names, dates, how old dead relatives would be today, what villages in Italy our ancestors came from, which in-laws worked where, how they died, and who are whose children, and where they are today. She had even visited Naples and distant relatives there. At 83, her mind clear and certain, Aunt Connie is a virtual walking encyclopedia of family history. “You want me to drop dead?” she said on thephone when I asked if she felt up to a visit.And soon we were settled in Aunt Connie’s kitchen, she in the kitchen chair with the pad on the seat and the armrests, me poised with pen and pad, video camera aimed at the table top. Uncle Al sat opposite me, patiently, uncharacteristically listening quietly as I asked the first question about my relatives. This silly question sparked my curiosity, so, I had to call Aunt Connie and ask to visit her. “You want me to drop dead?” she said on the phone when I asked if she felt up to a visit. “Are you trying to kill me?” She was, I knew, nowhere mad at me, or feeling threatened, her sarcasm hit its mark. She was the most boisterous of all my relatives.

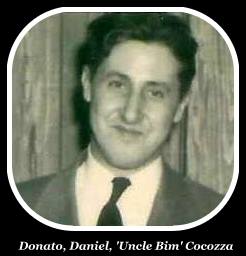

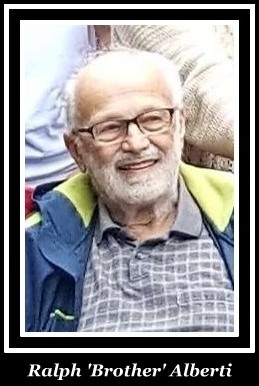

On my mother’s branch of the family tree she gave me uncles with names that were not their own. For instance, Uncle Jim was Vincenzo, Uncle Butch was Andro, Uncle Lou was George, and Uncle Bim was who knows? Aunt Connie would know. Uncle Bim and Uncle Lou were her brothers-in-law. The famous singer who took his mother’s name for professional reasons was also a Cocozza, although Mario Lanza was not a relative, as far as anyone knew. But there was one relative I could not account for, Brother. About all I knew about him is that he is older than me, never married and wore a beard. His was the first and only goatee in the family. “Who is Brother, Aunt Connie? And how am I related to him?” I asked. She sat on the pad in her kitchen armchair, hands folded nearly in prayer, eyes bright behind trade mark oversize glasses ready to answer the most difficult heritage question I could hurl.

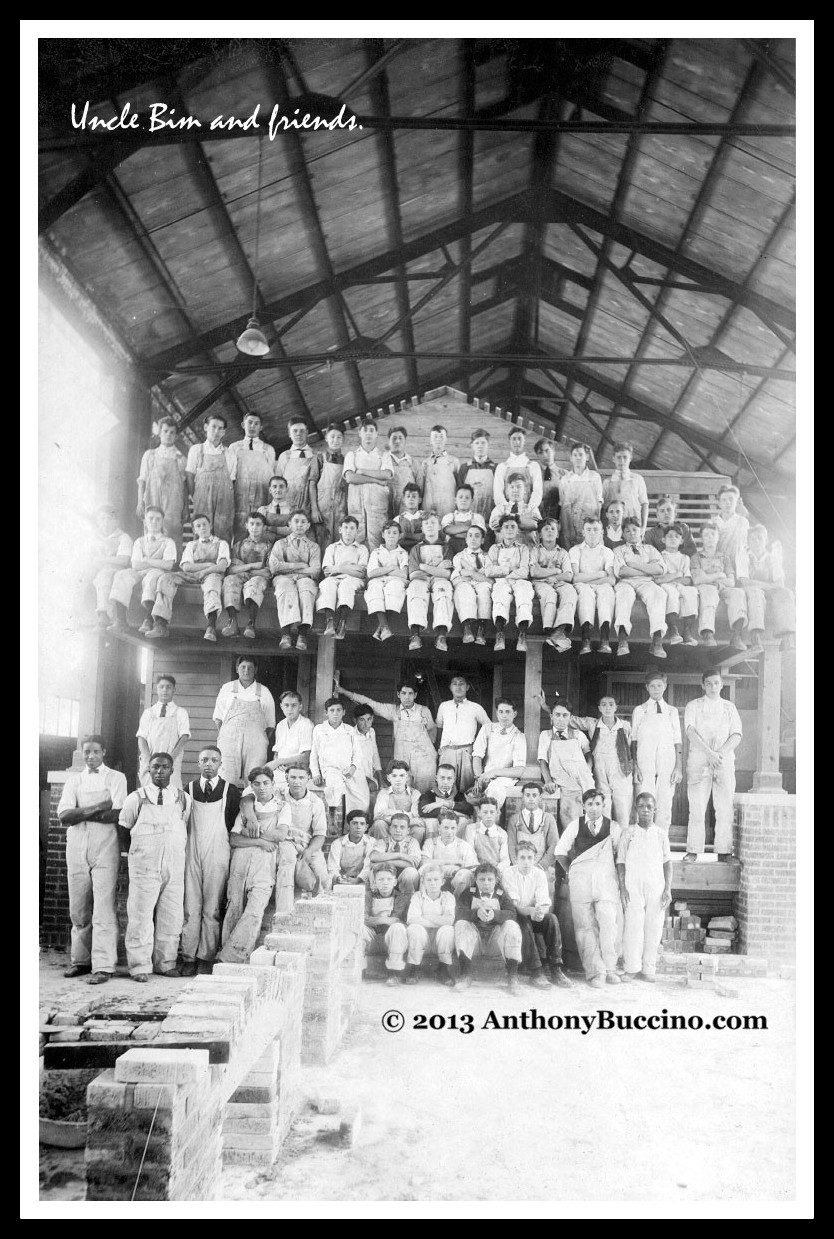

When Anna died of cancer at age 56, Brother lived with his father Frank Alberti, and my grandfather’s two bachelor brothers Frank and Uncle Bim Cocozza in the family house on 11th Street in Newark. Who is Uncle Bim? Officially, Donato was his first name, but he went by Daniel. Being the youngest of the boys, his older brothers would come in from work, or wherever, and give him a penny or other change. It appeared to everyone that Donato “always had money just like the guy in the funnies, you know, Uncle Bim.” And so, unofficially, even if he weren’t my grand-uncle, I would surely call him “Uncle Bim,” just as his brothers had since the Roaring 20s. On my way home I realized I hadn’t asked Aunt Connie one question, and now that I know who is Brother and what his real name is, I should have asked why he is called Brother. Another time, the good Lord willing. First published in The Belleville Post, Nutley Journal on November 4, 1993. Adapted from Sister Dressed Me Funny by Anthony Buccino

Read More A Father's Place, An Eclectic Collection Who is Brother, (who is) Uncle Bim?

WW2 Letters Home From The South Pacific La Storia: Five Centuries of the Italian American Experience by Jerre Mangione Una Storia Segreta - Lawrence DiStasi Finding Italian Roots by John Philip Colletta They Came In Ships by John P. Colletta Italian American Writers On New Jersey Identity Lessons: Contemporary Writing About Learning to Be American |

ANTHONY'S WORLDAnthony Buccino

Essays, photography, military history, moreNew Jersey author Anthony Buccino's stories of the 1960s, transit coverage and other writings earned four Society of Professional Journalists Excellence in Journalism awards. Permissions & other snail mail: PO Box 110252 Nutley NJ 07110 Follow Anthony Buccino WW2 Letters Home From The South Pacific

|

I

had come to learn about my relatives. When my folks were alive, it

never occurred to me to sit them down and write all this down. Now,

Aunt Connie’s memory was to be tested, for the sake of future

generations.

I

had come to learn about my relatives. When my folks were alive, it

never occurred to me to sit them down and write all this down. Now,

Aunt Connie’s memory was to be tested, for the sake of future

generations.  The four-room house was plenty, it had three bedrooms; one for four

sons, one for three daughters, and one for the parents. It had no

kitchen, but the Aliperto family never went hungry.

The four-room house was plenty, it had three bedrooms; one for four

sons, one for three daughters, and one for the parents. It had no

kitchen, but the Aliperto family never went hungry.

I tried to remember the last time I had been to Alva Street. When

was the last time I had seen Aunt Connie? Neither of us could say

whether or not if it was a wedding or a wake. It felt good to sit in

a kitchen that held so much history and family and warmth.

I tried to remember the last time I had been to Alva Street. When

was the last time I had seen Aunt Connie? Neither of us could say

whether or not if it was a wedding or a wake. It felt good to sit in

a kitchen that held so much history and family and warmth.  She seemed disappointed at the softball I had tossed her. “He’s your

mother’s cousin, my nephew. His mother, Anna Cocozza was your

grandfather’s only sister. But here’s the twist. His father was my

brother, Frank Alberti.”

She seemed disappointed at the softball I had tossed her. “He’s your

mother’s cousin, my nephew. His mother, Anna Cocozza was your

grandfather’s only sister. But here’s the twist. His father was my

brother, Frank Alberti.”