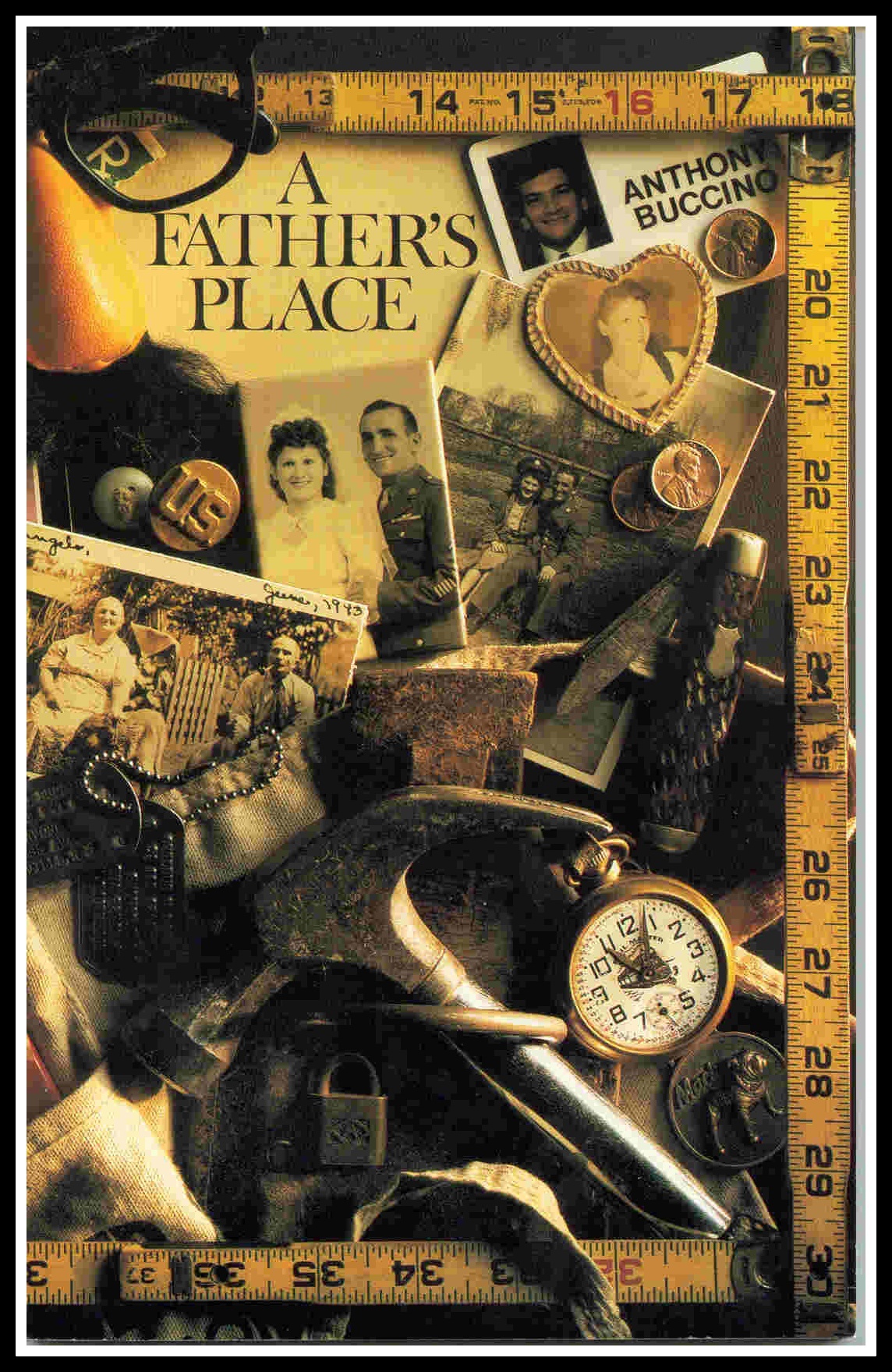

How Many Hammers Are Enough?by Anthony BuccinoWhy did I decide I had to count a hundred screwdrivers and two dozen hammers, every size plane ever made, and toolboxes up the kazoo? Dad, how many hammers are enough? |

|

|

Strange, it is, to sense the memories that suddenly swim to the surface like the picture in my head of my father as the ragtag kid who swam from the bottom of the Passaic River with a handful of mud, "See, wise guys? I really did swim to the bottom!" Dad was a good swimmer, a very strong swimmer.

It's not an inherited skill. It wasn't until my late teens that I

knowingly approached water that was deeper than my Adam's apple.

Swimming is something a dad should teach his son before the boat

starts to leak.

Building things was Dad's claim to

fame. He never took complete credit for a building or a house, but

he earned his pride in a job well done. His pride was of a true

craftsman who looked back every time and said, "I built it with my

own hands and tools. No one could have done it better."

I absorbed his patience and sense of

poetic justice, maybe from just being around him, definitely not

from direct tutelage. He did not teach with words. Questions always

seemed to annoy him. "Geeze, that kid asked a million

questions," he lamented after a neighbor's child finally went home.

The kid had found Dad's homing pigeons fascinating.

"Sure, you got to ask questions,"

Dad said, shrugging his tired shoulders.

But

Dad won't be remembered for his patience with little kids,

especially me. He was a good guy. He gave everyone whatever break he

could, especially if the guy had a good sob story. Mom always chided

him, "Ange, I don't see anyone giving you a break when you're out of

work for months at a time." He would look at her like a man who

had just found his kid brother without a nickel in his pocket. "But

Ree Ree," he'd say. It was his way and I do not think he ever

regretted it. It wasn't until I bought my own

house that I wished I had seen more of the way he worked. When I was

a child, the times I helped him all seemed to be the same.

"Hold this board for me, Ant, while

I saw it. … Where'd you put my level? … Ya feel like cleaning up

here for me?" The day we installed the drop stairs

for my attic I was trying so hard to be the carpenter he had been. I

was trying to do on one day what he'd had 40 years to master. I

finally asked why all the nails I was hitting were bending, yet his

drove straight and true. "Let the vibration quit," he

wheezed, his lungs nearly consumed by emphysema, "before you hit it

again." So I did and it worked. I was like a

child with a new toy. I found new relish in my labor. I just wanted

to drive nails all day. One little lesson Dad taught me made me feel

so good. I wondered though, why it took twenty-four years to learn

to drive a nail. All I did was ask, and he told me.

Dad had a

different wooden toolbox for every job. He built the best toolboxes.

They were sturdy, yet not so heavy that when loaded with tools they

could not be lifted by above average carpenters. He had even built a fake toolbox. It

looked like a regular toolbox from a distance, but close up, it had

six compartments for different penny weight nails. "Last night somebody broke into the

tool shed at work," he said at dinner, "took all the tools we had

there." "How did you work today without any

tools?" I asked.

He paused to decipher the question.

"Whoever had some tools in his car passed them around. Most of the

guys just leave their tools on the job instead of carrying them back

and forth every day. Then, again, some guys work side jobs. As a

rule, those guys keep tools in the car. Whenever I have a toolbox in

my car - I've always got an extra hammer or two. You can never have

enough hammers. … When I don't work, I don't get paid. It's that

simple. If nobody has any tools, then we all lose the day's pay."

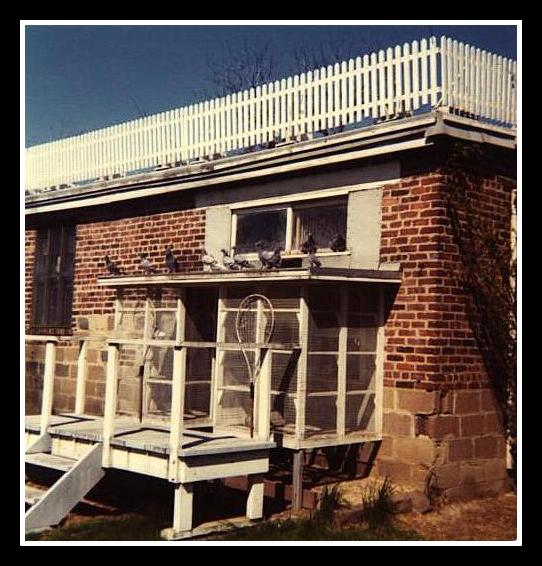

Cardboard drums of pigeon feed with

screened cut-outs for ventilation lined up like sentinels in the

garage outside the entrance to the coop. Inside, the birds watched

for the familiar face, the familiar jacket and the familiar hunched

stance of the man who fed them, the man they thought was God on

earth. These birds flew at more than a

thousand yards per minute from one to five hundred miles away to

return to the home Dad provided for them in his garage. Their mates

were here, their nests were here, and so were their eggs or squabs.

His 'boids' took baths in flat water

pans on our lawn. They ate gravel between the grass blades. Their

oil-slicked necks glistened under summer's sun. A hundred pigeons

lolling around the water like a Roman orgy. Dad knew each bird, who its parents

were and how well they had flown. He knew what to expect from each

racer by its pedigree and whether to keep it alive through winter to

the spring Old Bird racing season. A bird that did not perform in races

as it should have would have its neck wrung behind the closed garage

door. When we figured this out, us kids would stand outside crying.

Even the dumbest homing pigeon was

smarter than a roof rat or statue squatter. "Take one of those wild

birds ten miles away and you'll never see it again."

Dad trained his birds by taking them

on short trips to fly home, and then driving further and further

each week until they knew how to get home from at least ten or

twenty miles away. Most of the time the birds would be

home at the coop waiting when he pulled in the driveway with the

empty crates. I went along for the ride many, many times, counting

telephone poles and winking back at truck drivers high up in their

rigs at traffic lights. Some of the pigeons had become old

friends of mine. A few of the breeders were more than ten years old.

Whenever I found myself with an abundance of patience, I would stoop

low in the coop and the birds would feed from my hand. A light

pecking and a slight pinch was their way of telling me when the food

was gone. If I would be kind enough to allow, they would eat my

freckles. I learned at a young age how to hold

a pigeon so it would not fly away. Grasp its legs between the middle

and ring finger; palm the tail between thumb and forefinger. A bird

in this position is fairly helpless. I could turn it over. I could

hold it close. I could pet it. I could study the rainbow colors on

its neck. Before a race or training flight,

Dad checked the band number on each or both of the bird's legs. He

had put the permanent metal band on the leg when the squab was small

enough to cry for its mother and old enough to raise its wing in

defiance to Dad. For twenty years I competed with

those birds for Dad's attention. I knew them well. I knew a blue bar

from a checker, and a dark checker from a red bar checker. My

favorites were the blue bar splashes. They looked like an average

pigeon that had perhaps straddled under the ladder of a sloppy

painter. My favorite pigeons were the Judas

birds. With their wings clipped, the Chicos were thrown up to

flutter to the coop. That would encourage the racers to land sooner.

The Chicos were docile, and smaller than the homers, and could get

lost two blocks away. ***** Although Dad quit smoking years

earlier, the damage had been done. The fine white pigeon dust did

him no good. It had gotten too difficult to properly train them. And

though he never said it, he knew I wasn't interested in it being a

family tradition. He quietly decided to close up the

coop, sell the birds and all his supplies at an auction. There, I

went out and got milk when the supply ran low. Retired, with no pigeons, Dad

tinkered on his odd little projects. He built collapsible pigeon

crates for other flyers. He built a workbench in the cellar because

he couldn't take the cold garage in winter. Dad liked to go out for breakfast

early in the morning now that he was retired. Mom sent him off with

her blessings and slept in 'til 7 or so. She teased him about the

redheads he really was seeing instead of going to the diner for

breakfast. We all knew he loved redheads. Whenever he saw one on TV,

he'd howl affectionately, "Hey, baby doll!"

And he called lots of times to ask

my wife and me to come over and kill some time. "You know how it is,

Dad, what with the house and lawn and all," I found myself saying,

"we'll be over in a couple of days."

When we finally got there, we heard

the same song. He bemoaned the time we never spent together. Mom

admonished, "You decided to have pigeons while your son was growing

up. You can't have that time back again." I never argued. I just waited for

him to fall asleep in front of the TV. He slept best in front of war

movies and would stay asleep until someone changed the channel or

lowered the volume. ***** Somewhere in the Fijis, between

blasts of artillery, Dad, before he was my dad, began to smoke

cigarettes. A lot of other young boys did. That was war, one of

their sayings was, "if you got 'em, smoke 'em."

When the war ended, he kept on

smoking, for twenty years, two or three packs a day, no filters,

just the finest blend of Turkish tobaccos. His morning cough shook

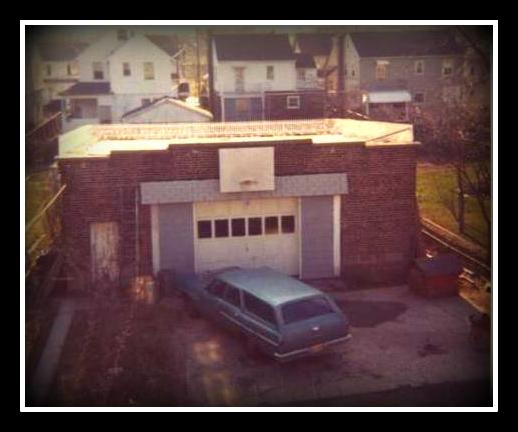

the plaster and woke the household. He quit smoking after so many years at the snap of a finger. It was amazing, especially when he let us know how much he had actually smoked. Until then, none of us ever counted, so one cigarette was pretty much like another. The first one of the day was the same as the fiftieth - what did we know from how many he had choked down along with sawdust and dirt from his job. IN THE GARAGE, water leaks into the

empty pigeon coop, spider webs seal nail kegs and water leaks from

the roof onto plywood stacks. Fighting away anger and tears, I

invaded this somber legacy of a man who too late learned he loved me

and too late learned I loved him. I felt a shallow, guilty need to

account for what had been left behind before time and rust and rot

consumed it all. Why did I decide I had to count a

hundred screwdrivers and two dozen hammers, every size plane ever

made, and toolboxes up the kazoo? Dad, how many hammers are enough?

You've left enough extension rulers to last for my great

grandchildren! Would you still walk a mile for a Camel?

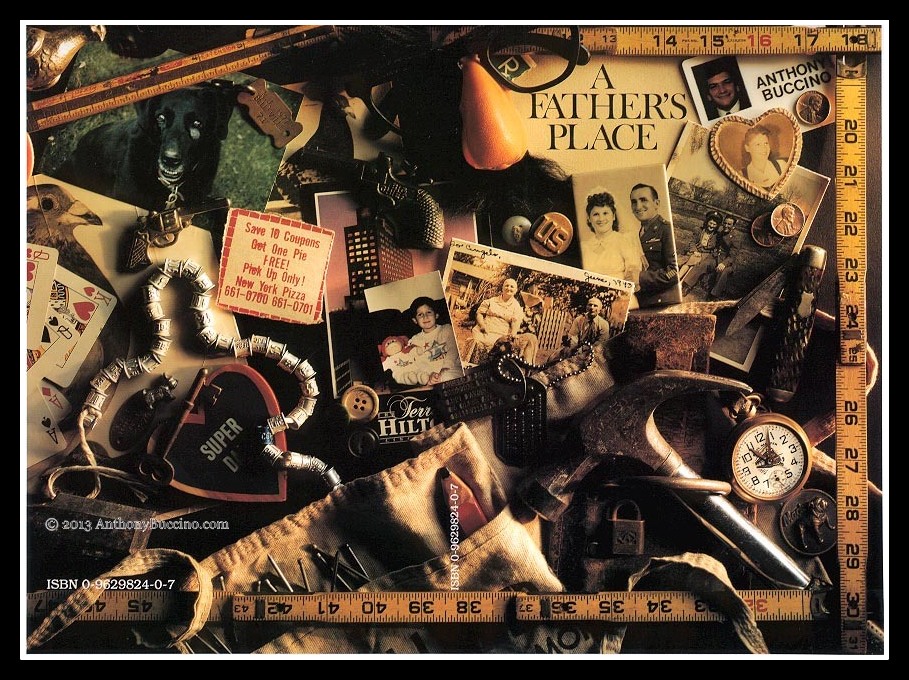

And, by the way, Dad, I had a little

girl. I know you would have loved her. She's a redhead. First published in Bloomfield Life on Oct. 27, 1983. Adapted from: A Father's Place, An Eclectic Collection My Super Bowl Tradition: Psyching Up for the Carpenter Bowl Read more: A Father's Place, An Eclectic Collection WW2 Letters Home from the South Pacific For My Father Nutley Sons Honor Roll Remembering the Men Who Paid for Our FreedomBelleville Sons Honor Roll Remembering the Men Who Paid for Our FreedomBelleville and Nutley in the Civil War - A Brief History WW2 Letters Home From The South Pacific

Shop Amazon Most Wished For Items

Web site will receive a stipend for purchases through the Amazon link Support this site when you buy through our Amazon link. |

ANTHONY'S WORLDAnthony Buccino

Essays, photography, military history, moreNew Jersey author Anthony Buccino's stories of the 1960s, transit coverage and other writings earned four Society of Professional Journalists Excellence in Journalism awards. Permissions & other snail mail: PO Box 110252 Nutley NJ 07110 Follow Anthony Buccino This Seat Taken? Notes of a Hapless Commuter

Shop Amazon Most Wished For Items

Support this site when you buy through our Amazon link. |